An interview with Susie Alegre

Our founder, Dawn Walter, interviewed Susie Alegre for the Response-ability.tech podcast. Susie is a human rights lawyer whose book, Freedom To Think: The Long Struggle to Liberate Our Minds, was published by Atlantic Books in April.

Our founder, Dawn Walter, interviewed Susie Alegre for the Response-ability.tech podcast. Susie is a human rights lawyer whose book, Freedom To Think: The Long Struggle to Liberate Our Minds, was published by Atlantic Books in April.

She talks about freedom of thought in the context of our digital age, surveillance capitalism, emotional AI, and AI ethics. The podcast episode was released on 24 May 2022.

This is a lightly edited version of our conversation. You can also watch the full 30-minute interview on YouTube.

Watch the interview

Why did you write the book?

Let’s start with why you wrote the book, and why our freedom of thought is important in terms of human rights in the digital age.

I’ve spent the last 20-25 years working in human rights in various different capacities, including working on issues related to privacy and the digital world, looking at human rights and counter terrorism. But while I knew the law, I knew the arguments, I delivered the arguments, I wrote tons of policy briefings and press releases, and all those things that you do as an activist.

I’ve spent the last 20-25 years working in human rights in various different capacities, including working on issues related to privacy and the digital world, looking at human rights and counter terrorism. But while I knew the law, I knew the arguments, I delivered the arguments, I wrote tons of policy briefings and press releases, and all those things that you do as an activist.

I suppose, I’ve never really felt something so viscerally as I did when I first read about the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and what I read about the question of political behaviour on micro-targeting. This idea that companies say that they can understand who you are, what your personality is as an individual, based on your data, scraped off the Internet, off social media sites, and use that information to then target and manipulate you, to change how you might behave on voting day. Not necessarily changing you from a Remainer to a Leaver, but if you are, for example, a Remainer and maybe make it less likely that you’re bothered to get off the sofa, or if you’re a Leaver, giving you that extra push to get out there, if that is the desired outcome.

This idea that our minds could be for sale, wholesale, felt so viscerally disturbing.

And when I read about it, and it wasn’t that it was Cambridge Analytica. It wasn’t about the personalities, which is what the story became a year later. It was this idea that our minds could be for sale, wholesale, in an election environment and that this is actually very common. It goes far beyond Cambridge Analytica, it goes far beyond Brexit or Trump. It’s something that is increasingly used an election environment.

And to me this idea that my mind might have been hijacked in that way, whether or not it was, I’ll never know. But the idea that it could have been and that maybe that made me feel complacent that I had curated complacency through my Facebook newsfeed where everybody agreed with me and everything was going to be great, just felt so viscerally disturbing that I thought this is something that goes beyond privacy.

Now, privacy is crucial, privacy is a gateway, right? But to me, it felt that it was something more intimate, that this was about freedom of thought, and when I first started to look at freedom of thought, I discovered that there’d been very little written about it, certainly nothing at that stage about freedom of thought in relation to Big Data.

And so I wrote my first article about it [Rethinking Freedom of Thought for the 21st Century] in 2017 in the European Human Rights Law Review. But I couldn’t let it go. I couldn’t just leave it at that. I spent the next couple of years talking to people about it, raising the idea everywhere I could and trying to chip away to get traction because I thought, if this is something that’s upset me so much, maybe it’s something that will make other people understand why these issues matter and why we need to worry about them in our digital future.

This tendency for technology to be designed to understand how we think and feel, how we operate on an individual level, but escalated to a global platform.

And the more that I looked at it, the more that I realised, that it’s not just about Cambridge Analytica, it’s not just about politics. This tendency for technology to be designed to understand how we think and feel, how we operate on an individual level, but escalated to a global platform.

So understanding and potentially manipulating us as individuals on mass, in our billions, to change society is something that you see in all areas. You see it in criminal justice, you see it in predictive policing, in the security field, but you also see it in how your weekly shop is being used to analyse what kind of a person you are, and how that data is then going into a massive soup of data that may tell companies how risky a person you are, which might have an impact on your ability to get credit, on your ability to get insurance, on the kind of jobs you’re served up when you go online looking for a job search, what recruiters might think about you.

By focusing on this idea that it’s our minds that are fair game, I hope it will shift how we, as societies, look at and think about digital futures.

It really goes across all aspects of our lives and that’s why I felt that I wanted to go beyond academic articles, beyond policy papers, and write a book that would be accessible to anyone, not just people working in this domain. It doesn’t have huge surprises for people who have spent the last 20 years working on privacy in terms of the things I’m talking about. But what I hope was that, by focusing on this idea that it’s our minds, it’s all our minds, that are fair game in this environment, that maybe that would shift how we, as societies, look at and think about digital futures and that way we could bring about change.

What is freedom of thought?

Can you explain for us what freedom of thought is and the difference between an absolute right and a qualified right?

So the right to freedom of thought and the right to freedom of opinion have two aspects initially. There’s an inner aspect, what goes on inside our heads, and the outer aspect, which is where we express ourselves or we manifest our beliefs. And what I’m talking about in the book is that inner space, and that inner space is treated quite differently to the expression of our opinions.

We hear a lot about free speech and freedom of expression in the digital world, and that is a really serious issue. But freedom of speech can be limited for things like protecting public health, protecting the rights of others, protecting national security. So there are justifications for saying, actually, you can’t say that, or you can’t say that in this particular environment.

But what goes on inside our heads is treated differently. It is, as you say, what’s called an absolute right to have freedom of thought and freedom of opinion inside our heads, and that’s kind of crucial to what it means to be human. And there are very few absolute rights.

Your rights to freedom inside your own space, inside your own head, is really fundamental to what it means to be human.

The two classic absolute rights are the prohibition on torture in human and degrading treatment, and the prohibition on slavery. And if you think about sort of slavery, torture and the idea of losing your rights to freedom inside your own space, inside your own head, all of those things are really fundamental to what it means to be human. And all of them have that quality that, once you’ve lost them, you can almost never get them back.

The two classic absolute rights are the prohibition on torture in human and degrading treatment, and the prohibition on slavery. And if you think about sort of slavery, torture and the idea of losing your rights to freedom inside your own space, inside your own head, all of those things are really fundamental to what it means to be human. And all of them have that quality that, once you’ve lost them, you can almost never get them back.

And so absolute rights are protected differently. Absolute rights are protected in a way that says that, if something amounts to an interference with that right, you can never, ever justify it. So you can never have a reason for interfering with an absolute right.

Having said that many of the issues that I talked about in the book of flagging a direction of travel, they wouldn’t necessarily amount to a violation of the right in the strict kind of legal sense. But what I wanted to do was to scope out how technology is trying to get inside our heads, and to understand where the limits to that right should be, where the limits are, where you can say, actually this far and no further, technology cannot reach any further inside the mind.

How the powerful try to read our minds

If we look back in history, there are plenty of instances, as you show in your book, of those in power using their power to break or read minds, through various means. Can you take us through some of those historical examples?

Absolutely. When I started to look at the history, I realized that while there’ve been developments in philosophy about what freedom of thought was, and ideas, particularly coming out of the French Revolution, the Enlightenment, great ideas about what freedom of thought might mean, but in practice, for most of us, for most people in history, they didn’t have freedom of thought and they certainly didn’t have a legally enforceable right to freedom of thought.

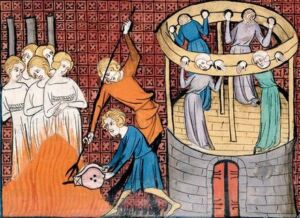

And so, a couple of the areas I looked at which affect ordinary people, if you like, rather than martyrs of thought and philosophy, one of the areas that is hugely shocking is when you look at witch trials and witch hunts through the ages, even up until the present day in some places. Looking at the thousands or millions of people around the world who have been accused and found guilty of witchcraft, not based on anything they’ve done, but on inferences about what’s going on inside their head. I mean, how on earth you can prove you’re not a witch is a very big question.

And so, a couple of the areas I looked at which affect ordinary people, if you like, rather than martyrs of thought and philosophy, one of the areas that is hugely shocking is when you look at witch trials and witch hunts through the ages, even up until the present day in some places. Looking at the thousands or millions of people around the world who have been accused and found guilty of witchcraft, not based on anything they’ve done, but on inferences about what’s going on inside their head. I mean, how on earth you can prove you’re not a witch is a very big question.

One of the big problems is these inferences about our inner minds is being drawn from our data.

And that’s one of the problems, I think, that stretches through into technology. And the drafters of international human rights law recognized this problem, that violations of your right to freedom of thought and belief don’t necessarily need to get your thoughts or beliefs, right?

You know, if the witchfinder decides based on your black cat and your wart that you are a witch, that you are a believer, and that you are doing spiritual things which are affecting other people, it doesn’t matter if that’s complete rubbish, you’re still going to be burned at the stake.

And that is one of the big problems, that inference is being drawn from our data. These inferences about our inner lives, which are based on outer signs, are being drawn together and categorised as reflections of what’s going on inside our heads.

Ewen Cameron used the power that he had over these people to carry out experiments to see if he could wash away what was going on inside their minds.

A more recent example I looked at was the way psychiatrists had used science to try to get inside our heads and to change the way our heads worked. One example, which is particularly shocking, was a Scottish psychiatrist operating in Canada, Ewen Cameron who was connected to CIA thought-manipulation research, looking at ways to control the human mind as part of the Cold War battle to get inside our heads, in order to be able to extract information, question spies under duress, and which spilled over into the war on terror and the way that terrorists latterly have been interrogated.

But Ewen Cameron wasn’t looking at CIA operatives. He wasn’t looking at international spies. He wasn’t looking at suspected terrorists. He was carrying out experiments on ordinary people who had been brought into a psychiatric institution for depression, for postnatal depression, for anxiety, for other psychiatric illnesses, and he used the power that he had over these people to carry out experiments to see if they could essentially wash away what was going on inside their minds and replace it with something else. Using things like sleep deprivation, white noise, these kind of techniques to really get inside the head, wipe it away, rearrange the furniture.

But Ewen Cameron wasn’t looking at CIA operatives. He wasn’t looking at international spies. He wasn’t looking at suspected terrorists. He was carrying out experiments on ordinary people who had been brought into a psychiatric institution for depression, for postnatal depression, for anxiety, for other psychiatric illnesses, and he used the power that he had over these people to carry out experiments to see if they could essentially wash away what was going on inside their minds and replace it with something else. Using things like sleep deprivation, white noise, these kind of techniques to really get inside the head, wipe it away, rearrange the furniture.

But as I say, what’s really shocking is that this was happening to ordinary people walking into a psychiatric institution, hoping for help, looking for help. And many of them have talked about the devastating consequences that this had on their lives and on their minds for the rest of their lives.

Why researchers shouldn’t be experimenting with facial recognition AI

One of the current threats to our human rights, to our freedom of thought, is facial recognition technology, particularly when it claims “to read our minds and personalities through our faces” (p. 178), and predict such things as our sexual orientation. Can you explain for us why researchers shouldn’t be experimenting with facial recognition AI (pp. 178-179)?

I think there is a difference potentially between facial recognition that just recognizes you as you, and facial recognition that’s being used to interpret who you are on a deeper level, if you like. And whether that is emotional AI trying to work out that you’re lying, or whether it is, as you say, this supposed research that claims to be able to tell what your sexual orientation is or what your political opinions are based simply on a photograph of you.

When you look at that kind of research, and the researchers say, often, that the reason they’re carrying out this research is to show how dangerous this technology is, which is possibly laudable. But when you do this research, you are effectively opening Pandora’s box.

Saying that you’re doing the research to show how dangerous it is, while essentially putting this technology out into the world, doesn’t absolve you of the consequences of that research.

When you say, I can show that you can tell the sexual orientation of a person by a photograph run through an algorithm to tell you with a certain percentage likelihood whether or not this person is gay or straight, for example, it doesn’t really matter whether that research works. If that technology that you have researched and developed can then be used around the world in places where homosexuality, for example, may still be a capital offense in some countries, it’s certainly illegal in many countries around the world.

Researchers can’t design a project to explore torture techniques to see whether or not they work.

Just saying that you’re doing it to show how dangerous it is, while essentially putting this technology out into the world, doesn’t absolve you of the consequences of that research. And there really is a need for a much more serious ethics review to be done around research to look at the longer-term consequences of what that research can do.

You know, researchers can’t design a project that’s going to explore torture techniques to see whether or not they work. And essentially designing research in order to violate a person’s right to freedom of thought, particularly when that could have discriminatory consequences or existentially devastating consequences for democracy worldwide, then that research really shouldn’t be happening in the first place.

Why human rights law is ‘ethics with teeth’

You suggest that we need to move away from the discussion of ethics “back to the law, specifically human rights law” (p. 300), that ethics are simply a “good marketing tool”. Has the focus on AI ethics been a distraction, do you think, when we should have been focussing on human rights law the whole time?

I think it has to a degree, and that’s not to say that there aren’t fantastic ethicists working in AI, or that it’s not important. And as you say, my view is that human rights law is ethics with teeth, but one of the dangerous things in the current environment is that human rights law is itself being undermined and eroded, both in legal terms but also in the way we think about it.

So we’re constantly being told that human rights law is a problem, that human rights law is for other people. And one of the things I want to do with the book was to show how we all have human rights, we all need them, and we mustn’t ever be complacent about them.

One of the dangerous things in the current environment is that human rights law is being undermined and eroded.

Human rights law to function as it should needs to be able to work in practice. And as I say, it’s one of those things that, by focusing on ethics, you make it appear optional and you take away the power, potentially, of saying, well, actually, there are these legal constraints and we need to be serious about them.

For human rights law to work in practice we need to make sure that the institutions that enforce it are able to work in practice, and that’s something that today around the world is very much under threat.

One of the examples that I used in the book, and it’s the only example I know of to date, where a constitutional right, the right to an ideological freedom in Spain, which is the equivalent to the right to freedom of thought or the right freedom of opinion in international law, was used in a legal case, in a legal discussion, which also talked about privacy, striking down a law, which allowed for political micro-targeting, for the use of voters’ data to be used for targeted advertising and profiling in Spain.

One of the examples that I used in the book, and it’s the only example I know of to date, where a constitutional right, the right to an ideological freedom in Spain, which is the equivalent to the right to freedom of thought or the right freedom of opinion in international law, was used in a legal case, in a legal discussion, which also talked about privacy, striking down a law, which allowed for political micro-targeting, for the use of voters’ data to be used for targeted advertising and profiling in Spain.

But that was able to be used, that discussion was able to be had, because Spain has a human rights institution that can bring constitutional challenges about the law in its own right. And it has a constitutional court that can consider whether or not all laws are in line with the Spanish Constitution, which is where you find human rights law in Spain.

And so that is an example of a court being able to consider human rights arguments in detail, and at speed because there’s a human rights institution that can bring that case to court. But where it becomes problematic is if you’re relying on individuals in countries where litigation is expensive, or difficult to bring, where you don’t have the same powers in human rights institutions.

One way of reducing the currency of human rights law is refocusing on ethics.

And so while I say human rights law is ethics with teeth, we need to make sure that those teeth are not rotting in the mouths of our democracies, if you like, we need to make sure that it’s used. And one way of reducing the currency of human rights law is refocusing on ethics, talking about voluntary self-regulation, things that are nice to have, rather than things that we need to have, to make our societies work properly.

Data privacy as our right to freedom of thought

As you note (p. 138), the inferences being made about us, the data profiling, the manipulation…it’s practically impossible to avoid leaving traces of ourselves, it’s beyond our personal control, and privacy settings don’t help. You suggest (p. 300) that by looking at digital rights (data and privacy protection) in terms of freedom of thought, “the solutions become simpler and more radical”. Can you explore that a bit more for us?

It goes back to that question of the freedom of thought being an absolute right. And so, it being, I mean, another way of looking at it is the absolute core of privacy is mental privacy, so some people talk about it as mental privacy, mental privacy is essentially that right to freedom of thought.

And so when you think about this absolutely protected core, then you can start to think about things that must never be allowed, rather than looking at ways of regulating things that are happening and that will develop, which is the way that sort of privacy and data protection law has worked historically.

So if you look at something like surveillance advertising, the fundamental oil of what Shoshana Zuboff calls the surveillance capitalism business model, that is based on an idea that it should be okay for advertisers and marketers to gather so much information on us to understand, not only what kind of a person we are, what our demographic is, but to understand our psychological vulnerabilities, to understand how we’re feeling minute by minute. And for that to be sold, auctioned, on an open market so that advertisers can tailor and direct advertising to us to manipulate how we’re thinking based on a momentary analysis of how we’re feeling.

So if you look at something like surveillance advertising, the fundamental oil of what Shoshana Zuboff calls the surveillance capitalism business model, that is based on an idea that it should be okay for advertisers and marketers to gather so much information on us to understand, not only what kind of a person we are, what our demographic is, but to understand our psychological vulnerabilities, to understand how we’re feeling minute by minute. And for that to be sold, auctioned, on an open market so that advertisers can tailor and direct advertising to us to manipulate how we’re thinking based on a momentary analysis of how we’re feeling.

Now to me that whole idea, whether or not it works in practice, but that whole idea is a violation of our right to freedom of thought. And so if I’m right in that and you look at this question from that perspective, you’re not looking at what specific bits of data you can use to inform surveillance advertising, you’re just saying surveillance advertising that relies on an analysis of what is going on inside your head in order to manipulate you as an individual should never be allowed.

If you look at that from freedom of thought rather than how you’re managing the data, it’s about saying there are some things that your data can never be used for.

That’s not the same as targeted advertising based on context. So saying okay, here’s somebody who’s looking a camping website, we’re going to sell them a tent. That is completely different to advertising that says, well, here’s someone who is clearly feeling a bit low now because it’s 3:00 in the morning, they’re scrolling through a miserable Facebook feed, and maybe that’s a good time to sell them online gambling, for example, because they’re feeling vulnerable.

All those are two very, very different propositions. So, if you look at that from freedom of thought rather than how you’re managing the data, it’s about saying actually there are some things that your data can never be used for. And that turns it around. Rather than just saying, there’s some bits of data that can’t be used, or there are some ways of processing the data that can’t be done, or you’ve got to explain how your data is being used. Rather it’s just saying you can’t use data in order to interpret someone’s feelings and manipulate them for advertising, whatever it is you’re advertising.

Mary Fitzgerald, who reviewed your book in the Financial Times, said that reframing data privacy as our right to inner freedom of thought might “capture the popular imagination” in a way that other initiatives like GDPR have failed to do.

Absolutely. That is my hope and that is the bottom line for why I wrote the book.

Follow Susie on Twitter @susie_alegre, and check out her website susiealegre.com.

You might also be interested in:

- Our conversation with anthropologist Veronica Barassi who campaigns and writes about the impact of data technologies and AI on human rights and democracy.

- The Future of Privacy Tech with Gilbert Hill.

- Martha Dark, co-founder of Foxglove, who spoke to us about their work to make tech fair for everyone.

- Freedom of thought in the digital age. Our first podcast interview with Susie in 2020.

The Response-ability Summit, formerly the Anthropology + Technology Conference, champions the social sciences within the technology/artificial intelligence space. Sign up to our monthly newsletter and follow us on LinkedIn. Watch the talks from our events on Vimeo and YouTube. Subscribe to the Response-ability.tech podcast on Apple Podcasts or Spotify or wherever you listen.